#python #neural search #Jina

An AI-powered search engine in just one line of (stupidly dangerous) Python

Published Jul 21, 2021 by Alex C-G

If you like this post, be sure to check out my other lifehack: Save a fortune on pedicures (by chopping off your feet with a breadknife)

Hey everybody! Welcome to another episode of let’s misuse technology in new and stupid ways! Today we’re going to look at how to take an amazing technology like neural search, and misuse it in a way that a rogue user query could delete the contents of your home directory. In short, do not try this at home. At least not the one-liner bit. Using neural search on the other hand is pretty damn cool.

If you want to skip ahead, you can check out all the code on my repo.

What is neural search?

Neural search is all about smooshing together search technology with deep learning neural networks. In short, the neural networks understand the semantics of what is being searched, so if you search “cat”, matches for “kitten”, “feline”, etc would come up. Or “Chairman Meow” for that matter:

Sure, traditional search frameworks can do that too, but they need a whole book of rules. And if you want to change the language, you need to rebuild around a new rulebook. In neural search there’s no rulebook, just a neural net. So unplug your English neural network, plug in a French neural net and then searching “chatte” will bring up “chaton”, “féline” and so on.

It’s not just languages though. Neural nets can understand all sorts of things, like images, audio, video, or even amino acid chains. And if a neural net can understand it, you can build a search engine around it.

We’re going to build our search engine using Jina, an open-source framework for building search applications that use any kind of data.

Grok the concepts

Before jumping into the code, we need to understand a few concepts:

- Document: (a) The thing you want to search through, your data (in this case, the CSV above), (b) The search term you use to search your data (e.g. “vaccine”)

- Flow: The pipeline for processing and searching your data. It’s made up of Executors

- Executors: The individual modules that make up a Flow. Each one performs a different task like encoding a Document, indexing it, etc

- Jina Hub: An “app store” where you can download modules to process your data (so you don’t need to write them by hand)

Build your search engine

First up we’ll build the actual search engine. We’ll do this in more than one line of code (for the sake of our sanity), then one-line-ify it later. It’s still as short and simple as possible, clocking in at under 30 lines of code (including comments).

Create a virtual environment

We’re already talking about stupid things in this article, and one stupid thing to do is letting your project libraries potentially interfere with your system libraries. We’ll get around that by creating a virtual environment and work inside that. In your Linux or Mac terminal:

mkdir search_engine

cd search_engine

virtualenv --python=python3.8 env # 3.7-3.9 are okay

source env/bin/activate

Install Jina

Next we’ll install our requirements:

pip install jina[standard,hub]

This installs the standard package of Jina, along with Jina Hub which lets us use neural networks and other modules in just a few lines of code.

Download data

Since we’re building a search engine, we need something to search. Let’s use a small COVID-19 Q+A dataset.

mkdir data

wget https://raw.githubusercontent.com/alexcg1/jina-shortest-program/master/data/community_20.csv -O data/community_20.csv

Write the code

In your text editor or IDE of choice create a new file called sensible.py (since we’re not being stupid just yet!) Then we can import the stuff we need:

from jina import Flow

from jina.types.document.generators import from_csv

Create a DocumentArray to store the Documents. In this case, each line of the CSV is considered one Document, and we process and index the title field. The other fields are stored as metadata in the Document’s .tags.

with open("data/community_20.csv") as file:

docs = list(from_csv(file, field_resolver={"title": "text"}))

Create a Flow (the search pipeline). We’ll also set up the REST gateway to get data in and out:

flow = Flow(port_expose=45678, protocol="http") # Set up REST gateway for searching

Add some Executors to the Flow. We’ll download these from Jina Hub to save us having to write them ourselves. For a simple search like this we’ll just use two Executors:

TransformerTorchEncoder- encodes each Document into embedding vectors. Words or phrases with similar meanings have similar vectors. You can find out more here.SimpleIndexer- creates an index of Documents and embeddings. Later we will search through this.

flow =

Flow(port_expose=45678, protocol="http") # Set up REST gateway for searching

.add(

uses="jinahub+docker://TransformerTorchEncoder", # Add an encoder. This is the neural net that "understands" your data, downloaded from Jina Hub

name="encoder",

)

.add(

uses="jinahub+docker://SimpleIndexer", # Add an indexer. This creates a searchable index of the encodings and metadata

name="indexer",

)

Open the Flow context manager:

with flow:

And then start indexing the docs we generated from the CSV earlier:

with flow:

flow.post(on="/index", inputs=docs) # Set the Flow to index

Once that’s finished, let’s block the Flow from closing, so we can actually search through the data:

with flow:

flow.post(on="/index", inputs=docs) # Set the Flow to index

flow.block() # Keep the Flow open, ready for user to search

Run your search engine

Back in your terminal:

python sensible.py

You should see a whole bunch of text scroll past. At the end there’ll be an endpoint URL.

Search your data

In another terminal window:

curl --request POST -d '{"top_k":10,"mode":"search","data":["vaccine"]}' -H 'Content-Type: application/json' 'http://0.0.0.0:45678/search'

You’ll get a ton of JSON back with search results and metadata. The results won’t be great in this case, since we’re using a tiny toy dataset for the sake of speed. The larger (and richer) the dataset, the better results you’ll get.

You can also use a simple frontend like this one written in Streamlit.

Crush it into one line of code

What time is it? That’s right, it’s stupid o’clock! Now comes the moment you’ve all been waiting for: the dangerous bit!

So, how do we actually do it? With our little buddy the exec() function. This should never ever be used. It essentially takes a string and executes it as Python code. For example, I would have slightly bad day were I to run this script:

evil_string1 = "import os"

evil_string2 = "os.rmdir('~')"

exec(evil_string1)

exec(evil_string2)

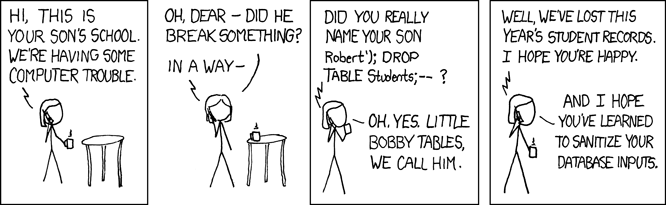

Why is this so stupidly dangerous? If your program takes user input, a user can submit a string of Python instead of (say) their name. And that Python code could be malicious. Think of it as “Bobby Tables” but for Python:

But that still doesn’t explain how to convert your code into a string in the first place. For that, we need to:

- Ensure you have a consistent quoting method (

"and') - since we’re going to wrap the whole thing in quotes we’ll get tied in knots if this isn’t consistent. - Remove any comments or use of

#(I’m sure there’s a way around this, but I’m lazy) - Escape all the text

- Wrap it in quotes

For most of this I use vim:

:%s/#.*//g # Remove all comments

:%s/\n/\\n/g # Convert new line characters to "\n"

:%s/\t/\\t/g # Convert tabs to "\t"

Then we just need to wrap it all in quotes and exec():

exec("your_program_here")

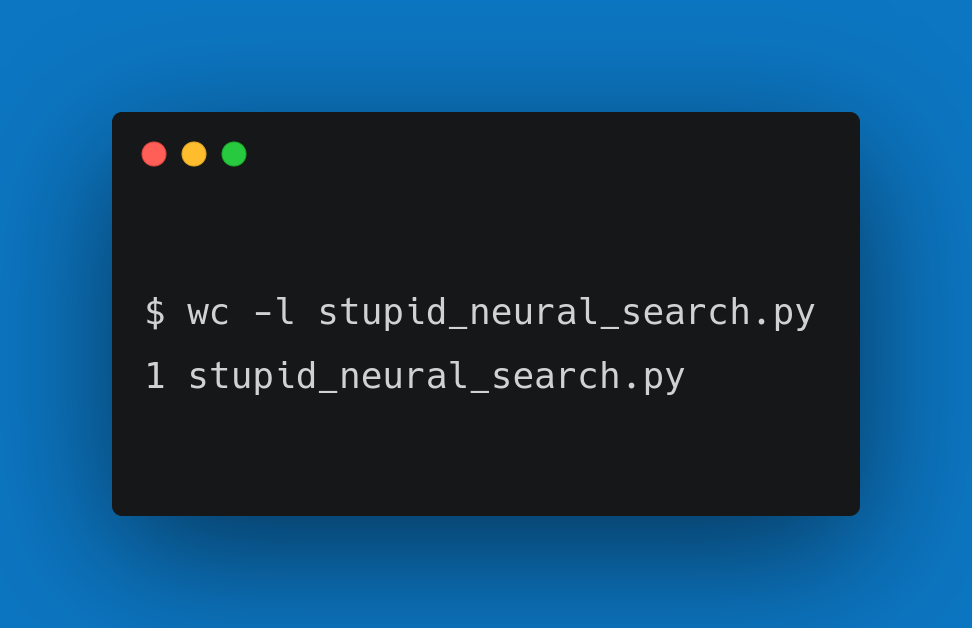

Save your program as stupid.py or similar, then go back to the terminal and run:

wc -l stupid.py

That command will spit out the line count:

1 stupid.py

And if you run python stupid.py you’ll get the exact same experience as running python sensible.py.

Ta-da. There you have it. Neural search in one line of (stupidly dangerous) code. Was this whole thing just about posting a dumb clickbait article? You bet. Was it a bit of a cheat? No. It was a lot of a cheat, but hey \n doesn’t technically create a new line in a file

Seriously, don’t ever use this method in your code. One-line-ifying everything makes things unreadable, screws up syntax highlighting and linting, and would play merry hell with version control systems (because they track changes on a line-by-line basis). Wrapping it all in exec() is just the dangerous icing on a towering cake of stupidity.

There’s only one reason (I can think of) to use this method. And that’s for writing clickbait like this. And hopefully it worked!

If you liked reading this (or are fuming about how ripped off you feel), head on over to Jina’s GitHub repo and throw a star their way. I’m their developer relations lead, so not only have I wasted all our time today, but I also have the sheer bloody nerve to try and shove our (rather lovely) product down your throats.

So, that’s all from me. I’m off to make pull requests to our competitors repos, optimizing all their code into one gloriously long line. Bye for now!

4#169 2018-2026, Alex Cureton-Griffiths